Monday, the Supreme Court handed down a notable decision regarding political redistricting in North Carolina. In a rather surprising 5-3 split, the Court struck down North Carolina’s most recent redistricting plan as unconstitutional in the case of Cooper v. Harris. The surprise came from Clarence Thomas, who broke ranks with his conservative compatriots and sided with Justices Kagan (who authored the majority opinion), Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor. The dissent, penned by Justice Alito, was joined by Roberts and Kennedy.

It’s a lengthy opinion and covers a fair amount of nitty-gritty regarding BVAP (black voting age population) percentages, the perils of vote dilution and preclearance requirements under the Voting Rights Act. At the heart of it is the fact that states often have to redraw their congressional district boundaries following a census to ensure compliance with the Constitution’s one-person-one-vote principle. North Carolina is no exception — its congressional map was redrawn in 1992, 2001 and again in 2011 — and it has a lengthy history of litigation to show for it. As both the majority and dissent note, Cooper marks the fifth time its 12th Congressional District has been before the Supreme Court – since 1993!

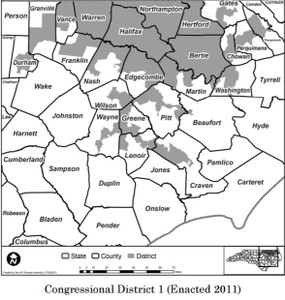

A quick look at maps of the 1st and 12th Congressional Districts (both of which are at issue in this case) might give a little insight into why challenges have repeatedly been mounted regarding their boundaries:

The Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment prohibits states from establishing voting districts by race, absent sufficient justification. When the Court takes up a voting district challenge such as this, it engages in a two-step analysis: First, voters challenging district lines must show that race was the predominant factor motivating any changes made. (Not just a factor, mind you.) If the challengers can demonstrate that, then the State must show that any race-based sorting it has employed serves a compelling interest and is narrowly tailored to meet that interest.

Following the 2010 census, North Carolina’s 1st District was found to be significantly underpopulated, necessitating a shift of just shy of 100,000 people into the district’s new boundaries. After the lines had been redrawn, District 1 became a “majority-minority” district, with its BVAP increasing from 48.6% to 52.7%. The State didn’t make any bones about its motivation in this instance. The legislators who chaired the committees responsible for preparing the new map intentionally pursued a racial target. They believe Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (which prohibits voting practices or procedures that discriminate on the basis of race, color, or membership in certain language minority groups) required them to do so, so as to avoid vote dilution. Since District 1 had a solid history as a “safe” district for candidates preferred by African-American voters, even with a white majority (sufficient numbers of white voters joined with black voters to support those preferred candidates), the risk of vote dilution was not enough to require it being made into a majority-minority district. The Court found that “North Carolina’s belief that it was compelled to redraw District 1 (a successful crossover district) as a majority-minority district rested not on a ‘strong basis in evidence,’ but instead on a pure error of law.” The State did not meet its burden of demonstrating the redrawn boundaries of District 1 served a compelling interest, and so its use of race as the predominant factor in redrawing District 1 was improper and the new map unconstitutional.

All eight justices (Gorsuch did not take part in this one) agreed as to the District 1 holding, though Thomas espoused a slightly different rationale in his concurrence. It is District 12 where they part ways, and not without some snark, which I’ll address below. To nutshell it, the State denied that it employed race as a predominant factor in redrawing District 12, but instead used political party affiliation. Not surprisingly, there is a remarkably high degree of overlap between race and party affiliation in and around the 12th District, which, as the above map denotes, boasts a long, narrow, “snakelike” body, and encompasses both Guilford and Mecklenburg Counties. Thus, the practical effect of the redrawn lines was a significant shift in the district’s racial composition, and it, too, was rendered majority-minority. Though the State presented evidence of the political rationale behind the changes (openly acknowledging they were designed to benefit the surrounding Republican districts – a strictly political gerrymander, which is permissible), the Court didn’t buy it. The State didn’t actually attempt to justify its attention to race (primarily because it denied that it had used race as the predominant factor.) Thus, the redrawn 12th District also was deemed unconstitutional.

But not without some rather pointed barbs being traded by the majority and the dissent. (I refer to these as “Footnotes of Snark”):

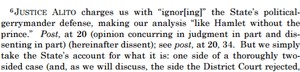

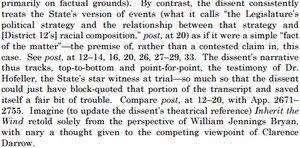

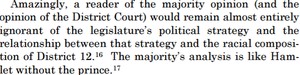

In fact, Alito, no shrinking violet, started off his opinion with some harsh words for the majority’s decision:

A precedent of this Court should not be treated like a disposable household item—say, a paper plate or napkin— to be used once and then tossed in the trash. But that is what the Court does today in its decision regarding North Carolina’s 12th Congressional District: The Court junks a rule adopted in a prior, remarkably similar challenge to this very same congressional district.

He has a point. The majority does seem to try awfully hard to find this redistricting impermissible. Bear in mind, gerrymandering has long been an issue for these districts – in large part because of the Voting Rights Act and the preclearance requirements outlined in Section 5 (the formula for which was struck down by the Supreme Court in 2013 in Shelby Co. v. Holder, so no longer applies, but was still in effect at the time these lines were redrawn.) And, as Alito points out:

After all, when the basic shape of District 12 was created after the 1990 census, the express goal of the North Carolina Legislature was to create a majority-minority district. It has its unusual shape because it was originally designed to capture pockets of black voters. (Citations omitted.)

But, as Alito also notes, about the 2011 boundaries, the legislature made it quite clear “that its objective was political: to pack the district with Democrats and thus to increase the chances of Republican candidates in neighboring districts.” He cites to a 1995 Supreme Court case, Miller v. Johnson, noting that, “Federal-court review of districting legislation represents a serious intrusion on the most vital of local functions…and the good faith of a state legislature must be presumed.” Thus, in his view, the courts “must be very cautious about imputing a racial motive to a State’s redistricting plan.” Not only that, but, “Under the 2001 version of District 12—which was drawn by Democrats and never challenged as a racial gerrymander— black registered voters constituted 71.44% of Democrats in the district.”

Alito makes a rather convincing case that Republicans are being held to a different standard than Democrats when it comes to political gerrymandering. Then, too, there is the fact that, “We have almost reached a new redistricting cycle without any certainty as to the constitutionality of North Carolina’s current redistricting map.”

Where this leaves North Carolina going forward remains to be seen. Undoubtedly, Republicans (and Democrats) will continue efforts to gain political advantage via the redistricting process. The primary difference at this point appears to be that Republicans are employing the electoral process to press their advantage, while Democrats are using the courts to do so.

For some additional insights on the decision, check out Rick Hasen and Daniel Horowitz.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member